Thanks: Kristin, Siobhan, Paul & Chris for your generous reviews and thoughts.

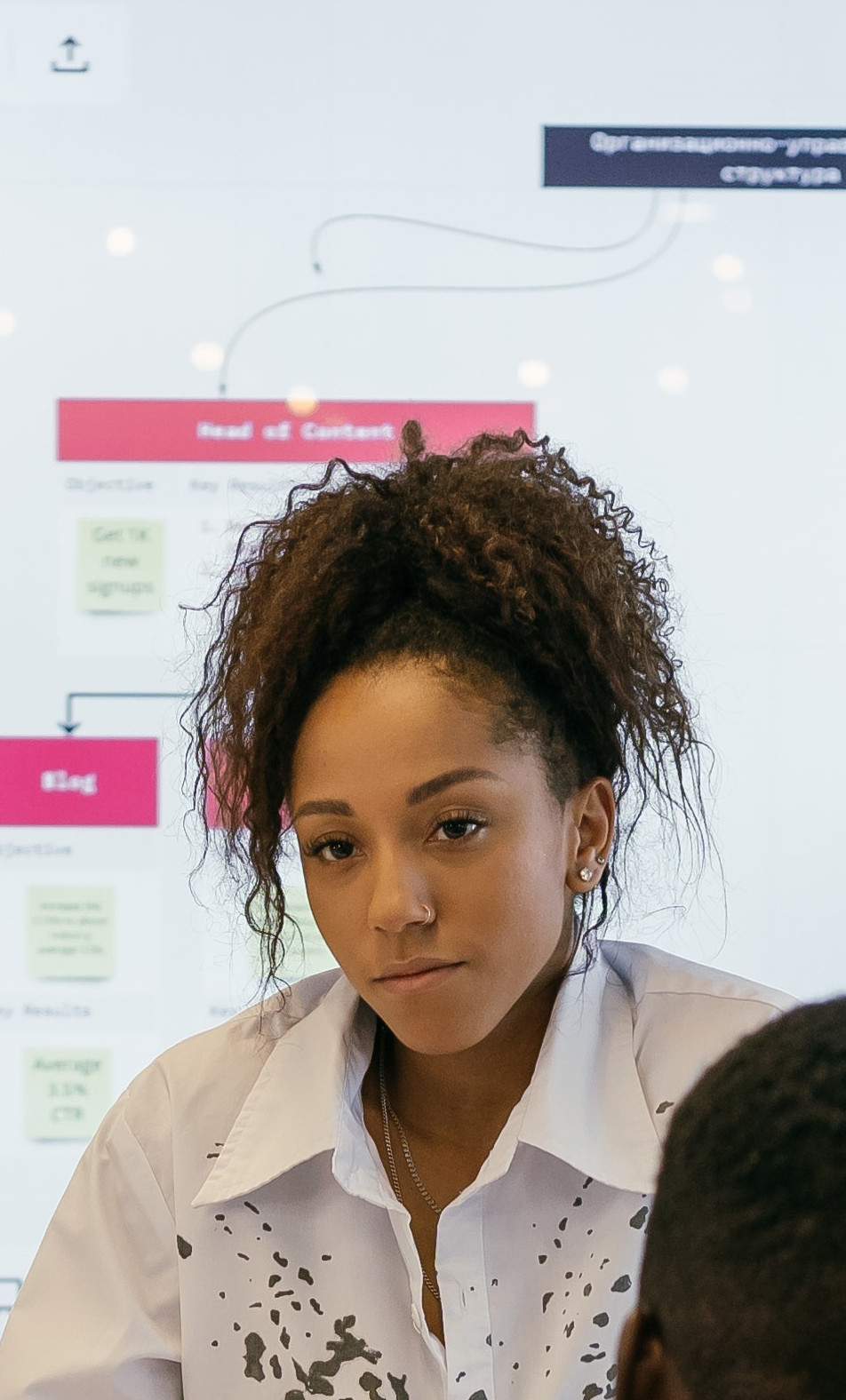

Working in government, a tech-focused non-profit, and running a SaaS all at once gives me a somewhat unique vantage point on software product development. For example, in considering whether a civic tech team in a government agency applies startup-oriented product development strategies or if they just think they do.

Civic tech is a fascinating place. Its leaders often say they are doing what start-ups do but inside government. But many of these folks haven’t paid their dues at a start-up. You have to wonder: are their teams following the path that drives private-sector product adoption? From what I can tell, some are, and some aren’t—if you want to judge for yourself, there is a tell.

The holy grail of customer satisfaction

In a start-up, from the top down, people are absolutely obsessed with a concept that brings clarity and purpose to their efforts: the achievement of “product-market fit.” A shorthand term for a crucial milestone, delivering a product that customers value deeply. Start-ups are in a race against time when it comes to this topic because they will inevitably run out of money without it.

But at least in a US government context, tech spending is not highly correlated to public engagement and utilization of digital services, which isn’t substantively measured anyway. So, when a leader in civic tech fixates on user needs despite the incentives to do otherwise, they “get it” when it comes to user goals driving product development.

That is the tell: when a civic tech leader prioritizes strategic user research.

Of course, not everything about being a start-up is worth emulating. But there is a lesson in centering user needs to provide measurable value. This has heightened urgency in civic tech, where the ultimate goal isn’t to make a profit but to support our neighbors and protect shared resources.

In government, there is also a “both sides of the counter” factor where product teams must understand users and the operational staff already engaged in meeting their needs who may be significantly under-resourced.

When you just know that you “just know”

Claiming to “just know” what users want is viewed as a wild idea in the start-up world today. No matter how intelligent or credentialed a person might be, the community has largely moved on from believing that smart people inside companies can understand customers without ever talking to them.

One example of a more humble approach to gaining insight through customer engagement is when start-ups intentionally ship truly minimal MVPs to get customer reactions to see how far they are along the path to product-market fit. On the other hand, in civic tech, too often, we see time and money spent on making something perfect before seeing if it's useful.

But let’s be honest: many government decision-makers don’t use or have never relied on the services their digital products pertain to. So, what can they reliably tell us unless they are informed by user research?

2 pixels on this side or that one—which side?

For structural factors, civic tech decision-makers tend to be solutionists. They see technology as the primary solution to problems and rush to apply proven tech strategies to lesser-understood systems or people-related challenges. They inadvertently fall into a “ready-shoot-aim” development model where a solution is prepared and implemented with perhaps some user research sprinkled in late in the process. Unfortunately, research can’t inform strategy when it gets tacked on; it becomes tactical at best.

At that stage, when a researcher says more than where to place a button, they may cause tensions if the scope of their user-validated objections is too much, as an implementation team might be under pressure to ship something and feel reluctant to embark on rework.

Sometimes, the problem is to discover what the problem is

By trade, I’m not a user researcher. I consider myself to be a designer and businessperson, yet most of my professional efforts have been in software engineering. Still, my passion is also research.

When thinking about this topic from an engineering perspective, I recalled Fred Brooks, yes, author of The Mythical Man-Month, but his often overlooked book The Design of Design, which provides additional enduring observations.

The Design of Design recognizes that “Sometimes the problem is to discover what the problem is” when framing how we usually don’t know the real obstacle at the outset of a project. Through

several case studies, Brooks shows how design requires creativity, understanding, feedback, and direction. As true today as it was then, without a strategically integrated design and research process,

there’s a significant risk—not just of building something of inferior quality—but shipping software that doesn’t address any important need.

Almost 50 years after Brooks, in Recoding America, Why Government is Failing in the Digital Age and How We Can Do Better, Jennifer Pahlka similarly reflects:

If software has been designed without an understanding of the needs of its users from the start, it is very hard to fix its deficiencies in testing, because the team has fundamentally built the wrong thing.

When this plays out in civic tech, it’s profoundly disheartening as many of us have left the comforts of the private sector to make a tangible and positive difference in society—not to build aimless software at the direction of people who don’t listen to the public or fifty years of ongoing expert guidance.

The first play

Turning to a more targeted resource, it’s no coincidence that “Understand what people need” is the first guidance of the USDS CIO Playbook, with another call for government agencies to recognize user needs and ensure services seamlessly fit into their lives.

I’ve wondered, nine years ago, when Ryan Panchadsaram and others published the CIO Playbook, why they led with strategic research and not Open-Source, DevOps, or Agile. The UK’s Government Design Principles also begins with “Start with user needs” in their similar guidance published two years earlier.

Now, I see the wisdom. Today, there is no significant internal conflict or external obstacle in adopting the aforementioned modern technical principles.

This is not true for strategic user research. Every day, strategic research gets put in organizations at the level below where it can have its intended impact. It gets compromised to strike a balance with less valid methods of more influential peers. Credible research takes time, so it gets sidelined by faster, less reliable alternatives. Product leaders look to user researchers to validate their pre-existing ideas, not to gain insights from non-obvious user needs.

What now?

I hope this post resonates with you. As a recovering solutionist, it’s taken decades and several product failures for me to earn the scars of building the wrong products. Still, it's not enough to recognize the urgency of strategic user research. To consistently apply this method and to stay relevant, civic tech organizations must position user research experts at executive and programmatic levels, empowering them to prioritize the most important guidance in product development: understand what people need.